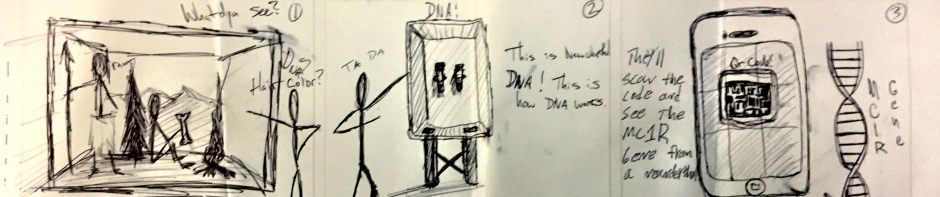

This has been a busy season for video games in NYC museums, what with the acquisitions announcement from the Museum of Modern Art and the Meade Arcade at the American Museum of Natural History (an upcoming interview here will focus on the two). Adding to the mix is the new temporary exhibit “Spacewar! Video Games Blast Off” (Dec 15, 2012 – Mar 3, 2013) at the Museum of the Moving Image, which I visited this weekend with my family. It is an excellent example of the importance of bringing video games into museum spaces and the substantial challenges involved.

My daughter playing Galaxy Force II

While the museum’s permanent collection has offered a wide range of video games to the public for many years, this new exhibit picked one theme – space-related games – through which to filter the history of video games. Space appears to be a natural theme to select, as the first video game, Spacewar! introduced both the space sub-genre and video games themselves.

The exhibit occupies a large room with video games of all sorts available in every corner. Arcade consoles. Computer terminals. Home video consoles projected on the walls. iOS games on an iPad and old handheld players. The exhibit clearly adores the device as much as the games themselves. Each game then offers signage that explains why the game was selected and its relationship to the genre.

There are many positive things to be said about the exhibit:

(Tech) Historically Accurate

The games are not simulations, emulations, or modern versions of old games. In almost every instance, you are playing the game as it was originally intended, from a technical level. From a social level, not so much. Yes, standing there plugging tokens into Missile Command and Tempest sent me back in time to mid-80s arcades and playing games at the roller rink. Put publicly playing Portal on the wall, which felt awesome, in no way reflected the smaller and more personal experience I have playing at home on my laptop. But the exhibit cares little about reproducing the sociology of video games, about how playing them affected our relationship with others and the people around us. It concerns itself with our relationship with the topic of space and how video games facilitated that conversation.

Strong Theme

And that conversation – video games as cultural objects reflecting our relationship over time with outer space – was interesting, and a strong theme throughout the exhibit. Missile Command and its relationship with Reagan-era nuclear fears is well described in the related signage, for example. The cultural event of the movie trilogy Star Wars was reflected throughout many game mechanics within the exhibit. In fact, the relationship between movies and games was a subtheme which could have been further developed. Movies inspired the first video game, which might/did affect the movie Star Wars, which produced its own video games, which later inspired other games and movies, etc. It is a complex series of relationships that would have been interesting to explore, especially in a museum dedicated to the “moving image,” and contrasted how films and games can use different languages to address the same topic.

Fun

There is no question, the exhibit is fun. I had to pull my kids away (but not my wife, who quickly grew bored and retreated to word games on her smart phone). And because of how the games are displayed, most people are not playing but watching other people play, at times reminding me of the social interaction that made video arcades such a vibrant cultural space. This meant, in part, that people who did not feel competent enough to play could enjoy the game play (and the space narratives) through watching others.

I did, however, notice a number of challenges involved with bringing video games into the exhibit space.

Placement Determined the Narrative

Reading all the game-associated signage, I think I could piece together the narrative of the exhibit. But, oddly enough, they were not physically associated with one another. They seemed placed, rather, where they were easier to play. Why were Portal, Super Mario Galaxy 2 and Yars‘ Revenge next to one another? Not because they were next steps in the same exhibit narrative but, it would seem, because each was being projected on the wall, and that was the best way to arrange that. Game play determined game location throughout the exhibit, not narrative, undermining the learning potential within the exhibit and threatening, at times, to appear as no more than a fun collection of games.

Now, that said, this is an easy critique to make without proposing alternatives. Videos games, in some ways, are site specific art that are being shown in an alternative context. We are asked to play arcades games without being in an arcade. We are asked to play on the wall of a museum a home video game designed for our television. After playing the iPad game, I literally left with my own version after downloading a copy to my iPhone. There is no simple answer to this challenge – of how to reproduce or respond to the designed experience video games offer, between player and space, and between player and other people – when transported into a museum hall. But Spacewar! the exhibit helps us to consider the pros and cons of one approach.

Technical Difficulties

I admired the curators intent to use original devices. However, as often as not, something was broken. Here are two videos which show each of my children playing a game and, in each case, the “fire” button was broken, presenting them with unresolvable conflicts:

They both had a great time, and were deeply engaged, yet, at the end of the day, they were playing broken games. We were not experiencing the game as the designers had intended. The screen to Star Wars had a projection problem. The Atari controller for Yars’ Revenge was broken. Portal and Super Mario Galaxy 2 both had been turned-off by previous players and it took tech support to turn both games back on. It made it clear to me that any museum, desirous of video games on the exhibit floor, would be well-served with tech support always available within the hall. Pricey, I would imagine, but dinosaurs don’t walk away from their platforms and Picasso frame doesn’t suddenly fog up. Games as a medium might just require more support. But this can serve dual purposes, not just making sure the games are presented to the public as intended but to also provide essential gaming literacy.

Gaming Literacies

The curators recognized that the visitors might need some help. 3/4 of a 2 page print-out – the only print-out for the exhibit – is covered by a glossary, which primarily focuses on defining sub-genres – e.g. “Corridor shooter” and rhythm game” – and technical terms like “wireframe”, “raster display”, and “polygon.” This reflects much of the technology love throughout the exhibit. However, what would have better served the visitor was a way to understand how game design, as a constructed medium, used the language of games in different ways to approach the topic. I fear that the general public’s lack of language to talk about games made the exhibit more shallow than it needed to be. Sure, they could play the games, or watch others play the games, but there were decisions made by the game designers, decisions which I presume were clear to the curators, and of great interest to them, but which were largely missed by the average visitor.

As a result, the exhibit, while fun and of interest to game connoisseurs, highlighted the challenges of bringing video game play into a museum and fell short of communicating to a general public the power of video games as more than just entertainment and cultural artifacts but as a unique rhetorical medium. Both the museum and curators should be commended for the exhibit, but it also highlights lessons that would benefit us all who wish to consider the role of video games in museums.

Akiva trying to play the first video game, Spacewar!

I am such a big space war game fanatic. I enjoy playing all sorts of online games, but mostly spaceship games. I usually play most of my online games at http://www.battlestar-galactica.bigpoint.com