I am excited to be the feature interview this month on the Digital Media and Learning Research Hub’s RiFF Expert Interview Series. It is a great interview and captures what I am thinking about eight months into the job. Check it out below:

Blending Digital Media, Badging, and Museum-Based Learning

A Few Moments with Barry Joseph

In October 2012, Barry Joseph became the Associate Director For Digital Learning, Youth Initiatives, at the American Museum of Natural History. In his new position, he explores the overlap between digital media and museum-based learning and how the mixture of the two can help young people learn science. We sat down with Joseph for a few moments to talk about how his work at the Museum is supporting young people in pursuing their passions through the creation of engaging and relevant learning experiences.

You came to the Museum after a dozen years innovating digital youth media programs. How have you combined that with informal science learning?

One of the things that attracted me to working at the Museum was its recent exploration in using virtual worlds to teach topics like marine life during the Cretaceous period, or the disappearance of the Neanderthals. In both programs, youth are essentially creating digital dioramas — populating them with their own 3D creations — to explore science concepts. At the same time, tools of science are put into the hands of youth, like when they build and project their own astronomical investigations using the same datasets and astrovisualization programs we use to create our public space shows in the planetarium. So now that I am here, my understanding of digital youth media has expanded to include tools of science, and I have shifted my focus to think about how they can be used to teach youth science practices and concepts, at times even contributing to authentic science research. For example, last January we worked with Museum scientists to teach youth how to use Morphobank, a global cloud-based tool used by researchers sharing datasets pertaining to Morphology (one way to study the evolutionary relationships amongst animals).

In what way is AMNH combining specific learning objectives with play in informal learning settings?

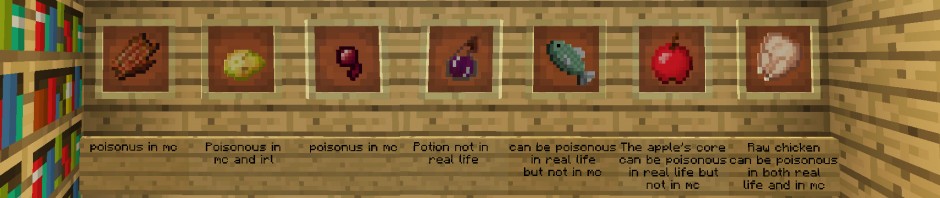

There are a number of things we notice when it comes to the question of game-based learning and what it affords us as a museum for new opportunities to expand our current educational programs and to connect with youth. It’s almost like an equation. The Museum knows science, youth know games, and games are increasingly being viewed as a way to teach science content and practices. When we put them all together, we’re combining the science expertise of the Museum, youth’s interest in games and games’ potential to teach science. In other words, the Museum + youth + games = 21st Century Science Learning. From a practical standpoint, there are so many things you can do with games from playing games like Plague, Inc. or Bone Wars with science content, critiquing science games that misuse science content, such as the role evolution plays in Pokemon, to participating in game-building activities, to offerings games that can be experienced in a blended way, both onsite and at home through mobile.

For example, last January we developed a new program that brought scientific content from our special exhibit, Our Global Kitchen, into a gaming environment. Partnering with TeacherGaming, we offered youth a modified version of MineCraft in which youth could explore, in an embodied way that games afford, the food production, processing and distribution system.

In your blog, you cite the National STEM Video Game Challenge as being a very nice model for what connected learning could look like. Can you say more about this?

An event like the National STEM Game Design Challenge not only speaks to what youth care about in terms of playing and designing games, but it also puts youth in the forefront by having them facilitate a majority of the NYC-based workshops. Yes, we were at an adult institution, but it was the young people who were teaching other youth the skills they needed to apply. When we ask what role museums like ours can play in the lives of young people, or about the role games can play, we can find an answer within the academic sphere of the connected learning model, which is really about the crucial role adults can play in helping youth see beyond the horizon of today. So on one hand, the youth taught their peers the basics of game design while we taught them how to recognize a system in nature that can be incorporated into a game mechanic.

One of the opportunities we have as a museum is to help young people realize that the digital media that is ubiquitous in their lives, which they might be using to keep connected with their friends or pursue areas of entertainment, can also be areas for informal science learning. The connected learning framework appreciates the role that a museum like ours can play by providing pedagogical experiences that are gaining currency as part of the learning required to be successful in the 21st century.

With all of the different opportunities for youth to learn, how do you help them navigate their way through these experiences?

Informed by our earlier prototypes that go back to 2010 through funding by the Hive Learning Network, we are now developing a more robust badging system. We anticipate it will help the thousands of young people across our dozens of programs connect the dots between skills developed and knowledge gained in one program and how they can be further pursued through different pathways within our education pipeline. One of the things that makes badges so exciting, and disruptive in such a rich way, is that they tend to make things that are traditionally invisible, visible. If a teen who completes a program is interested in authentic science practices, maybe her next step is to participate in a program where she can work with a scientist. Or maybe she cared more about the content area and wants to learn more about paleontology. Or maybe it was the artistic side that excited her and she can take a new program that focuses on the development of her creativity. A really robust badging system should be able to provide such a “just-in-time” scaffolding to guide her along her emergent learning trajectory.

The point of a badging system, however, isn’t just to offer trajectories; it also plays a role in validating their experiences. Badges help young people value the skills they are learning in our programs so they can develop the language to talk about what they’ve learned. When we tested our badging system in our Foodcraft program last January, the youth were able to talk about the connections experienced between a fun video game and an educational museum exhibit and how the two could support each other to create a deeply engaged learning experience in ways they weren’t able to express before entering the program.

How does maker culture fit into the mission of a natural history museum?

When we think about maker culture in the Museum, we recognize that there is a new interest in understanding how making can be both playing and learning. This is nothing new for science centers, and it’s why we see the close relationship between places like the New York Hall of Science and the annual Maker Faire, which they host. Experiential learning is what science centers are all about. But I work in a Natural History museum, which has a very different history. We are very much about our collections and the research behind them. The Museum is built on the work of more than 200 scientists who are doing research in the field and are bringing in tens of thousands of new specimens every year. It’s those objects and the science that comes about from studying those objects that forms our exhibits and shapes our education programs. Maker culture in that context is a little more challenging to think about because we are about studying and observing the natural world, not recreating experiences which related to it. We want young people to understand how to extract DNA from a strawberry or analyze a swab from their cheek to understand how DNA works, so making something, for us, has to align with specific science practices and concepts.

How do you build educational programs that support the development of these science skills?

In the context above, digital fabrication seems to offer us a really strong fit, more so than e-textiles or robotics. Digital fabrication is useful for us because the first step is learning how to see. It starts by learning how to look at what you just captured on your camera or phone and manipulating it, studying it in the 3D space, and trying to perfect it. You get to understand something very well by using your eyes. Those are skillsets that align very well with scientific practices. It allows us to take that final step within the digital fabrication process and print something – something you might otherwise be unable to actually see or touch, such as a nebula or bacteria, or something too fragile or sensitive like a dinosaur bone, and putting it in a form that you can actually hold in your hand.

Digital fabrication creates all sorts of interesting new pathways for informal science and for us to connect with youth. This summer, AMNH is offering a program called Capturing Dinosaurs where youth will have the opportunity to go into our bone rooms and make 3D models of our dinosaur bones. Did you know less than .01 percent of our dinosaur collection is on the museum floor? The rest of them are in rooms that few people get to see, but these youth in the summer program will get to go behind the scenes and see them, albeit for a very short time, just long enough to take digital captures. Once they capture them, they have to work with their captures for the rest of the program. Through this process, they will learn how scientists make decisions about what bones belong to which dinosaurs and how the bones relate to each other.

Once something is in a digital form, it might have value for others as well. Teachers might want to print out these models of dinosaur bones, which they couldn’t even see if they brought their students to the Museum, but now these youth can produce a form of digital media that can have an educational value for others. The Museum has always had a relationship with local teachers that goes back almost 150 years. Digital fabrication could create new pathways for the Museum to connect to teachers not just in New York but also around the country and around the world, by scaling out access to our collections — not the original physical collections — but replicas, which they can engage with both online and offline.

You grew up going to AMNH as a kid. Now, as an adult, it’s part of your everyday life. How does that feel?

I can’t believe I work at this museum. When I was a little kid, nothing could excite me more than going to the gems and minerals hall with my sister and rolling around the architecture of that space. It was great for sliding on. As a teenager, I came to the planetarium to see the lazer light shows. Then, in my 20’s, I would design my own games for my birthdays. I would have my friends get together, and we would do scavenger hunts by picking objects in the Museum and coming up with questions about them and breaking off into teams to find them. And in my 30’s I had my own kids and delight in supporting them to develop their own deep interest in the Museum (and, incidentally, coming up with their own crazy name for it, that became the name of my blog Moosha Moosha Mooshme.) So clearly, I have always had a lifelong relationship with the Museum, one which has grown as I have, and to work here now and to be able to participate in its growth into the 21st century, and specifically into the digital learning age, is a humbling experience. I feel deeply privileged to be able to bring my nearly 20 years working in new media and education into this community, and the museum community at large, to learn more about what has already been achieved in this space, and to collaborate with literally hundreds of remarkable people as we each make our contributions towards building the foundation of the Museum’s future, for both our children and the generations that follow.