Last Mother’s day, my two children and I took my wife to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to celebrate the day. We went to see the special exhibit, Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity, which highlighted the “vital relationship between fashion and art during the pivotal years… when Paris emerged as the style capital of the world.” We learned about the past, and had a nice day, but we also had a brief encounter that hinted at the future.

Exiting the exhibit we ran into MakerBot founder Bre Pettis (whose family apparently had the same idea about how to spend the day). The previous March Bre had announced, at SXSW, that MakerBot would be producing a new digitizer. After revolutionizing the consumer-grade desktop 3D printing market, this was a major play. “If you’ve seen Tron, this is kind of like what happens when Flynn gets digitized into the game grid,” he said at the tech hipster conference, “and then it makes it into a 3D model. Then you can make as many copies as you need.”

In other words, rather than spend 10-20 minutes taking digital photos, then another 5-20 minutes uploading the images and waiting for the 3D version to download, and then another 5 minutes to 5 hours fixing it up to get it print-ready, the Digitizer promised to streamline the process into a turn-table spin that would last no more than a few minutes.

So, when I saw him, I had to ask Bre about the Digitizer. And the seed was planted. He said it could come in the Fall.

My wait began.

This past summer we ran the summer program, Capturing Dinosaurs. We learned a lot about how far current technology could support a youth digital fabrication program. We also learned how long it can take, and how challenging it can be, to get a good capture. So I waited even harder.

In October you can imagine how excited I was when it arrived. I wanted it to shave days off of our scanning process. I wanted it to eliminate all future frustrations with digital fabrications. To be honest, I wanted it to solve climate change, eliminate disease, and herald world peace.

So, yeah, I was a little disappointed at first. We had not yet arrived at the world promised in Star Trek. After learning all the quirky idiosyncrasies of the MakerBot did I really now face a whole new range of quirky idiosyncrasies I had to learn? No, thank you. I now had to learn how dark colors absorbed laser light. I had to learn how to selectively apply baby powder. I had to learn how to scan in the dark!

At first, I kept getting it wrong, using action figures I “borrowed” from my son as test subjects (I find sculpted objects are easy to scan). The turn-table takes about 12 minutes to spin an object around twice, studying it with its red laser to build a mesh (the collections of points in space that define the object) then extrapolating and filling in any missing pieces. While it spun away I could do whatever I wanted, on the computer or anywhere else. That made it easy to experiment. And before long, my disappointment began to wan and my success rate increased.

We (Euijin, an intern from NYU, and I) then turned our attention to Museum objects. First, we checked out some anthropology objects from the Education collection. These are part of the 15,000 items that once were loaned out to school teachers and now remain as a rich repository for use within our on-site educational programs. We focused on hand-made objects, which we presumed would increase the rate of success, as it would avoid the challenging shapes and holes nature likes to throw in.

Now I am starting to get kind of impressed. It didn’t work every time but, when it failed to make a perfect scan, all we had to do was trash it and have it try again. And when it DID make a good scan, it was awesome. But still, the challenge of learning the ins and outs of guessing the RIGHT way to place the object on the scanner – should it face towards the laser light or look at it from an angle? – seemed tedious. And unnecessary. The Latin American Jaguar Mug (above) was almost mocking us in its unwillingness to have BOTH of its ears captured. It took Euijin probably a dozen scans before he just HAPPENED to place it just SO on the scanner to allow it to capture both ears.

Still, I stopped doubting. I had recovered from my initial disappointment that it wasn’t a fifth dimensional time node (the source of all power). I was starting to be charmed.

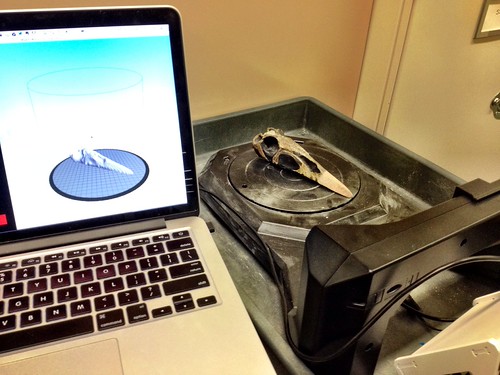

Our next test, as documented by the good folks at Gizmodo, took us into one of the Museum’s bone rooms, where we store all sorts of cool fossils. The goal for the day: scan some pterosaurs. I won’t rehash the details, as the article gets it right, but as another test of the digitizer, it was a big success. The pterosaur was placed on the turn-table and around it went!

We now knew how to work it. We could tell which objects would scan well and which might not. We just needed a practical proof of concept. And then one came knocking on our door.

Julia, the manager of our Sackler Educational Laboratory for Comparative Genomics and Human Origins, had a request. They were designing a new activity for high school students. The teens would be challenged to use forensic anthropological techniques to look at skeletal remains to determine its age, sex, body mass and the stature of the deceased. However, they needed an extra mandible (the lower jaw) for the youth to investigate. A complete second skull might run about a $1,000. Could we make a copy?

Of course, we said, and we tried. And failed. The level of detail required – to see the lines between the teeth, for the teeth to be flat – was just not coming through. And we were not interested in taking multiple scans and then stitching them together and cleaning them up in a program like Meshmixer. We just wanted the Digitizer to take care of it all for us – just take the object, let me get about my business, then return a perfect scan. Julia rejected the mandible copy we’d printed. It just wasn’t good enough to be used in an educational capacity.

And then it all worked. A new update came out for the Digitizer, conferring a remarkable new feature on the software: Multiscan. We were freed from having to twist ourselves into pretzels trying to get everything right into just one scan. Now, after the first scan, if that left jaguar ear was missing, no problem! We could turn the object, KEEP the first scan, but now add a second scan into the mix. The Digitizer software is brilliantly designed to identify where the two meshes overlap to both strengthen the core scan and incorporate the new elements. Still want another scan? No problem. Flip that sucker over to capture the bottom, hit the button, and 12 minutes later the third scan will be incorporated into the first two.

Now, THIS is what I’d been waiting for all year.

Using the same technique, we scanned the mandible on one side, flipped it over to capture the bottom, then used some sticky clay to turn it 90 degrees, so the top of the teeth faced the laser light. After roughly 30 minutes we had it. I had never seen such fantastic detail in a low-end surface scan. And unlike my experience with photogrammetry, we were able to capture all sorts of organic curves and spaces that had previously proved illusive.

This time, Julia accepted the print. A few days later they were able to use it in the program and it was a big success.

And now I am a convert. The Museum owns two Digitizers. We still have plans for repeating programs like Capturing Dinosaurs in 2014, but now I anticipate these programs can get more done in less time, with less frustration, without wholly eliminating the need for photogrammatric tools (the Digitizer still has a small footprint and not everything can stand being moved). At the same time, it now seems feasible to develop new and shorter programs that incorporate digital fabrication, programs we could never have imagined pulling off without it, and a number of these programs are now in development (three this upcoming Winter and early Spring).

In about three weeks, the one year anniversary will arrive of the Museum receiving its first 3D printer. It has been an exciting year exploring the possibilities of using digital fabrication for informal science learning, pushing the envelope, and learning from our colleagues from around both the city and country. At the same time, the pace of change is dizzying (even for me), the rate of new possibilities expanding season by season, and I can hardly begin to imagine what I might report here a year from now. What will I say n December, 2014, looking back at the year in digital fabrication and museum-based science learning?

What are your predications?