When people ask me how my life led me to a career in digital media for learning, if I am feeling flippant I might say it all began when I was in second grade, in 1976, when the highlight of that year’s Scholastic Book fair was Edward Packard’s Sugarcane Island, which launched the Choose Your Own Adventure books (and for the next two decades sold more than 250 million copies).

When people ask me how my life led me to a career in digital media for learning, if I am feeling flippant I might say it all began when I was in second grade, in 1976, when the highlight of that year’s Scholastic Book fair was Edward Packard’s Sugarcane Island, which launched the Choose Your Own Adventure books (and for the next two decades sold more than 250 million copies).

These books taught me about multilinearity, about how to think about narrative structures, about reader agency, about participatory reading, and more – all literacies required for survival in the digital age. And while others have played with the format in the decades since, few have captured the excitement and artistry suggested by those early books nor translated them effectively for adults… until now.

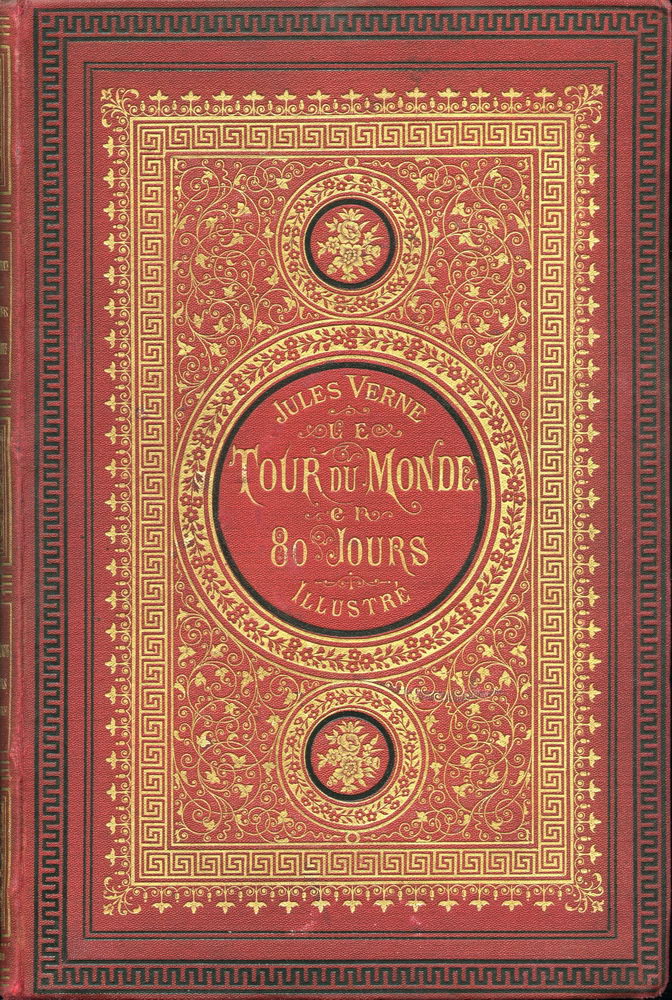

This summer a new app was released: 80 Days. It is hard to say what genre it fits into. Perhaps it suggests a new one. What is clear for sure is itsstory – this is a steampunk, Howard Zinn retelling of Jules Verne’s classic Around the World in 80 Days. Steampunk – because it imagines the Victorian era through this popular sci-fi genre, which imagines that steam-based technology introduced computers, robots and more into the late 19th century. Howard Zinn – because it takes the patriarchal, colonialist values of the Victorian era and replaces them with a shift in focus to women and marginalized groups (think The People’s History of the United States, but for the whole world). And yes, as you might suspect, the reading style is based on the Choose Your Own Adventure format, wrapped around a game (can you make the global journey in under 80 days?).

This summer a new app was released: 80 Days. It is hard to say what genre it fits into. Perhaps it suggests a new one. What is clear for sure is itsstory – this is a steampunk, Howard Zinn retelling of Jules Verne’s classic Around the World in 80 Days. Steampunk – because it imagines the Victorian era through this popular sci-fi genre, which imagines that steam-based technology introduced computers, robots and more into the late 19th century. Howard Zinn – because it takes the patriarchal, colonialist values of the Victorian era and replaces them with a shift in focus to women and marginalized groups (think The People’s History of the United States, but for the whole world). And yes, as you might suspect, the reading style is based on the Choose Your Own Adventure format, wrapped around a game (can you make the global journey in under 80 days?).

Luscious art and a lovely soundtrack (click above to play while reading this) complement what is essentially a skillfully crafted, sharply written, and brilliantly designed game. Or Book. Or gamebook. Or whatever.

The experience was not only deeply engaging but it left me wanting to re-read the original Jules Verne, re-watch the Jackie Chan film version, and learn more about the various points in history touched upon during my adventures. Its ability to first engage me in a fantastical world of wonder and then ignite an interest within me to learn more about the real world lead me to reach out to one of its creators, Meg Jayanth (@betterthemask), a freelance writer and game-maker living in London. I wanted to learn from her how she worked her magic and what we in the museum world might be able to learn from her process.

The experience was not only deeply engaging but it left me wanting to re-read the original Jules Verne, re-watch the Jackie Chan film version, and learn more about the various points in history touched upon during my adventures. Its ability to first engage me in a fantastical world of wonder and then ignite an interest within me to learn more about the real world lead me to reach out to one of its creators, Meg Jayanth (@betterthemask), a freelance writer and game-maker living in London. I wanted to learn from her how she worked her magic and what we in the museum world might be able to learn from her process.

Meg, you have written that “Writing historically shouldn’t be an excuse to fetishize outmoded ideas, but to invent better ones.” What does that mean and how did it shape the creation of 80 Days?

The problem I have with a lot of historical fiction, with a lot of period drama and steampunk, is that it enjoys the signs and symbols of historicity. Look at steampunk – we keep the victoriana – the bustles, the elaborate upper-class courting rituals, the arranged marriages and the stiff upper-lips – and elide away all the dirt and muck. The class politics are blunted in favour of a nostalgic enjoyment of silk dresses and soirees.

It’s a nostalgic, escapist vision – I am quite happy to go so far as to call it a fetishistic one. It’s a vision that has very little room for people of colour (who very much existed in Victorian Britain!), for queer people, for poor people. If they exist, they exist as victims. That seems dangerous and broken, that this is escapism, that this is fantastical. That glittering world of adventure and courtesy is built on oppression and suffering – the slave plantation and the Georgian ballroom are two sides of the same coin, but our reproductions of history so rarely acknowledge this.

How does this affect you personally?

As a woman, as an Indian, I can’t watch Pride and Prejudice and imagine myself as Elizabeth Bennet. I can’t help my mind turning to what kind of life I would have had, in Elizabeth Bennet’s world.

Even when historical works incorporate invention and fantasy – like in steampunk – the inventions are generally made by British or American gentlemen in top hats and cravats. Power is only ever given to a particular sets of hands.

80 Days very deliberately takes an approach in opposition to this: it focuses upon women, marginalized peoples, colonized peoples, servants. It allows them room to have their own stories, agendas and interests – to break out of victimhood or background dressing.

That’s why the regional power in the Americas of 80 Days is not the United States, still recovering from the Civil War, but Haiti.

It is why British, Dutch and French colonies in Asia are rising up and demanding independence, much earlier than they were in our own timeline.

It is why we chose to invent a Zulu Federation with steampunk weaponry capable of turning back the depredations of the European powers in the scramble for Africa.

It is why we twist history a little to allow the formation of a Persian Empire which counterbalances the activities of the “Great Powers” in the Middle East.

That is not to say that 80 Days pretends that colonization never happened, or ignores racism and oppression – I am very interest in the cost of “civilization,” and how it is constructed. Hopefully, we managed to let our stories `look at politics and violence and oppression without glorying in it. There are no loaded racial slurs, for instance – while it may have been historically accurate to include them, it did not feel responsible or necessary to do so (and in fact, felt quite damaging). That’s the line we tried to work.

While Choose Your Own Adventures can be fun, they rarely let the reader experience the story as truly self-directed and rarely fulfills the promise of reader agency. 80 Days offers one possible solution – the structure is determined by the game play elements but the choices made within the game support the story (the plot points, the characters developments, and more), rather than the other way around. As a result, I truly feel I am co-creating the story, not just following pre-set paths, and I can read the book over and over and still maintain that participatory feeling. How did your team solve these challenges?

I can only speak for myself here – but I think a huge part of this is that inkle team really understands narrative and writers. Unlike most game studios they are very explicit in wanting to tell a good story with their games, and their tools and processes are designed to make that possible.

I was brought on to the project very early on and had a good three months of writing and researching before they properly started development. And from that point there was a lot of communication – they were very open about letting me into the process of development, and sharing opinions about decision-making. The thing is – it’s a very small team. With a small team of people who are committed to making good work, it’s possible to do incredible things – I can’t heap enough praises on their process. There was an enormous amount of iteration – I think Jon and Joe (from inkle) were designing new mechanics and systems, and tweaking extant ones almost all the way up to launch. There were several points where the structure of the thing changed, and we rewrote everything to work – for instance, the Explore / Overnight system was an addition well down the line. Till then, there was just city content, which fired automatically when you landed in a location. It was a good change to make, and helped the player feel much more in control of what they were doing and why – but, as a writer, a bit terrifying to have to retrofit to! But decisions like that, I think, are why it feels so cohesive, and so directed an experience.

All the parts where shaken together, tested, sanded down and then reshuffled over and again to make the mechanism work smoothly.

Part of what intrigues me about your reinterpretation of Verne is, well… on one hand, you added a layer of additional fiction, exploring the technological wonders of an imagined steampunk past and their social and political consequences. On the other hand, your research clearly delved deep into the real world of the era to create an alternative history that introduces peoples and struggles previously unknown to the average reader. Why did you decide to go in both directions at the same time – fiction and nonfiction – and how did you strike a balance between the two?

There’s two sides to what I’m saying here: firstly, that authenticity does not exempt contemporary writers and artists from moral judgment. Just because there are historical injustices in a certain period, doesn’t mean that it is right to simply re-present them without commentary and context.

And secondly: a little history can be a dangerous thing. Often our idea of history white-washed, devoid of important women, robbed of the voices and ideas of marginalized people. But if you dig a little bit deeper, history is full of women, people of colour, LGBTQ+ people living, working, innovating and fighting. For a primer on this you absolutely cannot do better than Kameron Hurley’s excellent (and Hugo nominated) We Have Always Fought.

There are plenty of writers, historians and artists – many of them women, people of colour, and queer folks – destabilizing these stereotypical histories. Much of 80 Days is built on the work of people like Jaymee Goh (@jhameia), Benjanun Sriduankaew (@bees_ja) and NK Jemisin (@nkjemisin), and the work done in blogs such as Beyond Victoriana and The Steamer’s Trunk. I’d be utterly remiss if I didn’t mention Amal El-Mohtar’s wonderful essay Towards a Steampunk Without Steam, that absolutely catalyzed a lot of this for me.

Peeling back the layers of nostalgia and assumption is the right thing to do, but it is also a gift to the writer and reader/player: there is such an opportunity here, to tell unknown and surprising and challenging stories. To undo some of the violence of colonialism as we re-tell ourselves stories of it now (for pleasure). I think there’s some strange feeling that because this is a moral good, it is somehow boring but that couldn’t be further from the truth. Stories are suppressed because they are dangerous. Voices are silenced because they strike discordant notes.

I’ve written in some more detail about this very subject on my blog where I talk a little bit more deeply about the third axis in the balance of fantasy and history: that of respect for the cultures and peoples that I write about, and reinvent, and represent.

The history of many Natural History museums are often like the Victorian stories 80 Days is based upon. They are tremendously valuable for contemporary society but they bring with them histories that complicate how we might broaden more popular access to the full story. Do you have any advice for museums with these vast collections and archives about how we too can bring out the inherent wonder in what we offer while offering new perspectives into their complicated histories?

This is such a great question – I was a literature student, and so obviously the idea of vast archives and collections fills me with great and abiding joy. I saw a wonderful exhibition at SOAS in London recently, about Sikhs in World War One which did an incredible job of bringing little-seen collections and artifacts to life. What I loved about it was its focus on individuals – not necessarily important individuals – but individual Sikhs. Their letters home, their clothes and medals and mess-tins. The songs and poems sung by the wives at home. Photographs, paintings and sketches of Sikhs, Indians, Arabs, West Africans on the battlefields of France which demonstrated so clearly the multicultural nature of the war.

It’s a difficult task I think – to contextualize broadly and widely, without losing the individual. But focused, smaller exhibitions like this, which offer a mix of physical objects, photographs, audio, and written extracts – can be a real boon. You could really see the curator’s hand in the exhibit. I think that’s something that also shines through. I’d much prefer to see a museum exhibit that came from a particular perspective, that shows you that it is telling a particular type of story – rather than one that plays at objectivity or distance.

In museums we often try to engage our visitors be developing a “need to know.” One of my favorite outcomes from reading/playing 80 Days was the extent to which it made me want to learn more about the real world. Was that by design or accident? And, more importantly, how did you do it?!!

I’m so pleased you think that 80 Days made you want to learn about the people and places within it! I don’t know how entirely deliberate it was – though obviously, it’s something that I am very happy about.

I think – as I started researching I found myself so staggered and captivated by the real histories of places and periods that I thought were familiar, that some of that wonder leaked into the text. It’s a commonplace, but one I have found to be true: that history is much more incredible than fiction could ever be.

The thing about 80 Days is that it offers you snapshots of history – little glimpses into stories that unravel themselves and twist and turn and continue outside the your purview. That part is deliberate – you are a tourist, you do not get to be as important as the people that live there. You may be able to touch and nudge at a revolution, or participate in one – but it is not yours. I think there’s something intriguing about that – a story half told. You become interested in the fates of people that you meet and begin to care about. Even though I probably didn’t ever fully articulate it to myself, one of the rules we followed was: make people care first. Make it about the character first, and then the politics. If they care about this person, they’ll care about what they care about. There are, of course, people that care deeply about concepts like duty or country, but more often than not – there’s some human emotion, some history, some story, some community connection that makes them care.

I think that’s part of the reason why people care about the politics and history and propaganda speeches in 80 Days; it’s through the lens of “What does that mean to this person?”

Finally gamification seems to come into its own. Just like printed literature can be trash or “world class” it was time for games, like film, to emancipate themselves from the gregarious and point-and-shoot paradigm. Once this has been done successfully a few times, expect the floodgates to open and, what would have been a Shakespeare or a Kafka in their day, to now become a game designer. I think we are currently in the phase where “serious” movie directors shunned voice until that dam broke…

Love the alternate reality take–how you can use fictionalized narratives to provoke questions about the historical one. That has a lot of potential for museums, in well-considered contexts. Quite brilliant.