Last month at the annual AAM conference, this year in D.C., I had the pleasure to present on the use of augmented reality in museums with Diana Marques, who spoke about her research developing an app for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of National History, which put skins and movement on static bones exhibited in the halls, and explored the theoretical underpinnings of her research and app design. Afterwards, I grabbed her for a few minutes so she could share it as well with all of you.

Last month at the annual AAM conference, this year in D.C., I had the pleasure to present on the use of augmented reality in museums with Diana Marques, who spoke about her research developing an app for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of National History, which put skins and movement on static bones exhibited in the halls, and explored the theoretical underpinnings of her research and app design. Afterwards, I grabbed her for a few minutes so she could share it as well with all of you.

Hi Diana. Welcome to Mooshme. Please introduce yourself.

My name is Diana Marques. My background is in biology. I did a graduate degree in Scientific Illustration, so I combined science with art, which is truly my passion, communicating the messages of science through animation and through illustration.

And you’re working towards a new degree?

I’m getting a PhD now, in Digital Media. The program is a collaboration between the University of Porto, in Portugal, and the University of Texas in Austin. So, it’s a part Portuguese, part American program, and the research takes place at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, here in D.C.

Is there a particular hall that you focused on for your research at NMNH?

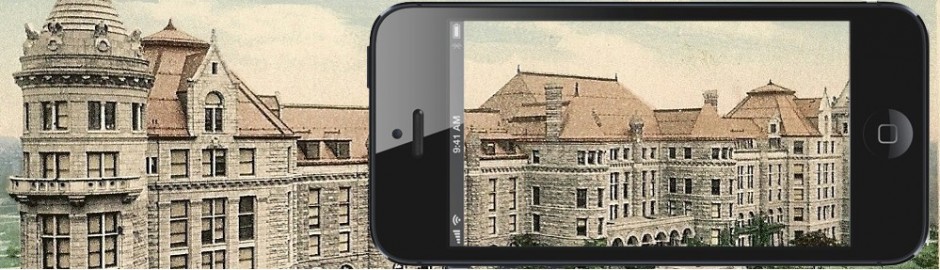

I worked on The Bone Hall which is a skeleton exhibition at the museum. It has close to 300 mounted skeletons, it’s the oldest exhibition at the Smithsonian. Actually, of some of the skeletons that are there on display, we have pictures in the 19th century, even before the Natural History Museum building was constructed.

So, this exhibit has had different iterations and the current design is from the ’60s. The trigger to create this mobile app that is part of my PhD was to bring a new life to the exhibit, because we knew that it wasn’t meeting modern audiences’ expectations anymore. You read the labels, they’re very specific; they are full of scientific terminology that’s just obscure. So people were definitely having a great aesthetic experience – you see very large skeletons, very small skeletons, you take great pictures – but the concepts of the exhibit were not carrying across.

So was there anything about the basis of the design of your research or the intervention you created that was built on previous knowledge or frameworks developed at Smithsonian to understand how visitors engage with exhibits?

We were aware of a framework that was developed by researchers at the Smithsonian called “IPOP”. IPOP is an acronym that stands for Ideas, People, Object and Physical activities. It was developed by Andy Pekarik and his team, at the Smithsonian’s Office of Policy and Analysis. There are several research papers that you can download from the Curator Journal. What the framework says is that we all have different levels of interest in the four dimensions, but in each of us, there is a dimension that’s dominant; so we can be categorized as being a People person, or an Object person, etc. They developed a survey instrument that it will tell you what your dominant preference is.

So how did you use that framework to form the design of the intervention you wanted to test?

We first selected 13 skeletons out of almost 300, based on conversations with curators at the museum. And we also picked the ones that would offer better stories across the four dimensions, for which we could develop a people story, an object story, an idea story, etc. So this framework not only provided us a way to design the app, it provided a guideline for looking for stories and the best skeletons to feature in the app. It also hopefully ended up giving us a product that’s more balanced and that appeals to more visitors.

The framework intends to be predictive, meaning that if the survey identifies you as a people person, you are expected to consume more people content within the app.

So are you saying that different people will see different things when they do it or just that you’re finding out their identities and afterwards you’re comparing it to what their actual actions were to see if they were aligned?

We designed it thinking, “a people-person will consume more people content.” And during the research stage of the project we compared the participants’ dominant dimension with the content that they actually consumed. Now, the framework didn’t prove to be predictive for us, but it has proven to be predictive in other settings, in physical exhibits, not within a mobile app. This was the first time that the framework was being applied to a technology tool.

But at the same time you were researching other things as well around augmented reality. Can you share what the user experience was around the augmented reality and what you found?

Augmented reality is the main drive of the research project – studying IPOP was more of a side project. Augmented reality and the visitor experience is the main theme of the dissertation and the way that we studied it was by developing two research apps in which one has the augmented reality content and the other one has the same content but without augmentation. For example, in the AR-version study participants saw the Mandrill skeleton being skinned, with its colorful fur aligning perfectly with the bones on display; and in the non-AR-version participants saw that same image on the screen but it wasn’t dependent on the presence and the triggering from the skeleton itself.

So this was the way for you to test the impact of AR itself, everything else being equal?

Exactly. The way to isolate AR as a variable.

What did you find?

AR drives a lot of interest, it definitely impacts the visitor experience. Visitors who saw the augmented content stayed longer with the app, stayed longer at the exhibit, they stopped more often. They looked intentionally for more augmented content. In the absence of it, people instead turned to the videos, so there was a clear content selection replacement; if AR was available to them, that was their main choice. Also, people who saw AR had much better ratings of their overall visit experience, they were much more positive about what they just went through. It’s not like the ratings weren’t good in the absence of AR, people were also pleased with the mobile app and with their presence in the exhibit, but they were even better with AR.

And were you also comparing it against an experience which didn’t have the mobile experience at all?

In a way, yes. Before the app was even developed, we conducted a smaller study in the absence of any digital enhancement, but that study was more simple, just looking at how many times visitors stopped at the Bone Hall, how long they stayed for, etc. So it’s not an exact comparison, because with the app, obviously, they’re going to spend more time at the exhibition and stop more often, they have an extra thing to do.

It’s an additional activity.

Exactly. That initial study showed us that only 60% of visitors going through the exhibition were stopping; the others weren’t even looking at the display cases, they were just using it as a passageway to get to somewhere else in the museum. So, definitely, we were able to change that and people now have — not only they have something more to see, but they are getting a lot more from it. And the interviews are very positive. They revealed a much deeper thinking about the experience than I anticipated Participants repeatedly mentioned learning with the app, and highlighted the multimedia contents being more suitable for visual learners rather than just the text next to the skeletons; the motion in the AR really added to their experience, so clearly it makes a difference.

So even though your research is over, can people still experience the app and do they need to be in museum to experience it?

Yes and no. The app is available in the App Store. The version that’s available now lets you download and print the triggers which are the pictures of the skeletons, so you can see the 10 augmented reality experiences wherever you are. You can also download a pdf of the pictures and trigger from a computer screen instead of printing the images.

If someone wants to learn more about the research, is it available yet?

The dissertation will be available in a few months, and journal articles will be published. The purpose of the study was primarily to share the information with other museum professionals, given that AR is a technology that has elicited so much curiosity and experimentation.

Thank you so much, Diana.

You’re welcome.