Today I popped over to the Inside 3D Printing Conference to see what a commercial conference looks like for digital fabrication.

My primary interest was the Transforming Education Through 3D Printing panel. It was led by Glen Bull, Professor at and Co-Director of the Center for Technology & Teacher Education at the University of Virginia Curry School of Education. He spoke from his role developing, in his words, “the nation’s first Laboratory School for Advanced Manufacturing, where students in the model school affiliated with the University learn science in a meaningful context as they use the latest manufacturing technologies for rapid prototyping of computer-aided designs.” It was fantastic to see the videos and demonstration projects of digital fabrication engaging middle school youth to learn engineering and science concepts. I wish, however, the conference had more than one educational use case to explore. (This project, incidentally, grew out of the Fab@School project, one of the MacArthur Foundation-funded HASTAC Digital Media and Learning Competition winners, of which my work on virtual worlds was selected in the 1st round and whose latest round launched the current explosion of interest in digital badging systems).

The second panel that struck my interest was Patents, Copyright, and Digital Rights Management in the Era of 3D Printing. The set up was intriguing: “What lessons can be applied from the experiences of the music, film and publishing industries as 3D printing digitizes distribution channels of physical objects as well?” Rather than a string of presentations, a panel of consumer advocates, rights holders, and legal experts took questions from the audience. I helped kick off the panel with the first question.

I asked them to respond to two not-so-hypothetical use cases. Visitors to a museum make 3D captures from their visit then share them online at Thingiverse, where others can print their own; visitors to Thingiverse have the right to modify their digital downloads and republish them, changing them in the process without having ever seen the original. The second case, related to the first, was a museum posting their own channel on Thingverse yet concerned about how others might modify and repost them.

The consumer advocate went first. He loved it. Simply loved it. This to him was an example of how creative innovations will flourish. The legal expert distinguished between objects in a natural history museum and an art museum, where the later has to deal with intellectual property issues. The New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, for example, team-up last year with folks from MakerBot to digitally accession 37 items and post them to a channel on a new Thingiverse “Met MakerBot Hackathon” channel. The files have been downloaded tens of thousands of times, and a number of derivative works have been posted, some to improve the originals, some to artfully interpret them, some to be silly. The final panelist addressed the desire that people will always have to pay to get a digital copy directly produced or authorized by the original museum and the opportunities there-in.

This last idea got picked up on the Twitter backchannel. First came a version of my question:

Brad then responded, reflecting on how giftshops are crucial to the finances of museums and suggesting one be created on Thingiverse:

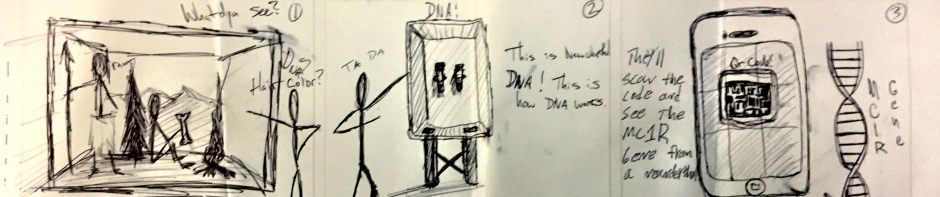

Jared then added to the conversation, suggesting QR codes be added to the signage next to objects in the museum linking directly to the digital file so you could print it yourself at home:

Finally, I was excited to hear the keynote from Peter Weijmarshausen, CEO and Co-Founder of Shapeways, even if I can’t pronounce his last name. Shapeways is the Dutch 3D printing service start-up company that opened its NYC factory last October, building towards housing 50 industrial printers that can support millions of consumer-designed products a year (and today announced $30m in new investor funding). “Everyone can be a creator,” he said, and showed how his company was part of a vast ecosystem making that happen. His final slide below re-iterated that point: “3D Printing for Everyone”: You want to design and print your own personalized ceramic coffee mug? Have at it. You want to design your fiance’s wedding ring and digitally fabricated the silver band? They can make it happen.

You want to design and print your own personalized ceramic coffee mug? Have at it. You want to design your fiance’s wedding ring and digitally fabricated the silver band? They can make it happen.

This “everybody in” message was in direct contrast to the opening keynote for the day by Terry Wohlers, the president of a consulting firm. Wohlers challenged the myth that everyone is going to own a digital printer. Sure, in the 70s, people who doubted those who predicted everyone would own a home computer were soon eating their words. But computers were different, he argued. They have enhanced and aggregated so many different activities into one device. But when it came to 3D printers he only had one thing to say: “Most people aren’t designers.” And that is true. At least for today. But what Wohlers is not taking into account is that digital fabrication tools are designed not just to enhance current artists but empower and inspire new ones. That is why 3D printers are not rising on their own but within the broader Maker Movement, which is not just offering artists and entrepreneurs new ways to distribute items for sale but creating tools to make it easy and accessible for people of all ages and backgrounds to participate.

So in many ways, the future – and I mean specifically the near-future – of 3D printing and digital fabrication relies on the success of the broader Maker Movement to create and support a culture of broad participation in design practices. And that, in part, is what excites me about bringing digital fabrication and these values into museum-based science learning, expanding the abilities of our next Science Generation to literally help build the future.

Pingback: Roundup and Wrapup: Inside 3D Printing Conference 2013 | 2literal